Mary's Grave on Wilkinson County Cemetery Site

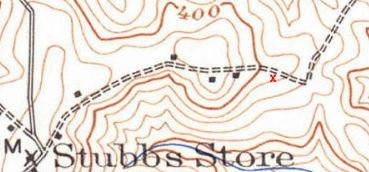

Below photograph of Gilbratar Mine is courtesy of Algernon Cannon. The view is to the west toward Washington County.

Mary

Patricia A. Collins Copyright 1986

All rights reserved.Reprinted with permission

of the author.

Atop

a lonely wooded hillside in central Georgia sits and old broken tombstone,

the last remnant of a memorial to a woman known only as "Mary."

The

time-worn epitaph reads: Mary, died June 25, 1862, Age 27. The mystery

of who she was, how she died and came to rest in such a isolated spot reaches

out from the past.

"We

refer to that hill as Mary's grave, " said Boyd Dennard, Superintendent

of Englehard Minerals & Chemicals' Gilbraltar Mine. "We go around it,

back and forth everyday, but nobody knows much about it," he said.

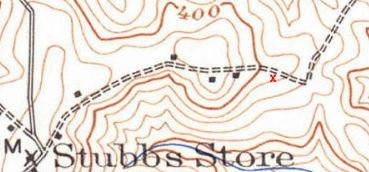

The

lone hillside located off Highway 112 in Wilkinson County sits in the middle

of a kaolin mining operation. The terrain surrounding that hill has dramatically

chanted over the past ten years.

Before

mining began, the abundantly timbered red clay hills dropped down

into a rich hardwood forest in the swamps of the Oconee River Valley. Three

years ago approximately 8,000 acres of that adjoining swampland were donated

to the University of Georgia for an experimental forest and the Beaver

Dam Wildlife Preserve.

"We are required by law to maintain the gravesite and an access road to

it," Dennard said. The State of Georgia passed legislation in 1919 concerning

regulations of burial sites and the mandatory maintenance of death records.

Since Mary's death predated that legislation, the solution to the mystery

seem questionable.

Records indicated that the land was bought from Georgia Kraft, who had

acquired it from Greer Land & Timber Company. "Apparently they purchased

it from a private land owner," said Ben Benoit of the Englehard Corporation.

The key to the mystery lay in finding the private land owner so that records

could be trace back to the owner at the time of Mary's death.

Although Wilkinson County was formed by legislative act in 1803, a permanent

courthouse was not built until after 1818. The earliest records on file

there date back to 1820.

"There have been three fires at the courthouse since it was built, " noted

the present Clerk of Probate Court, Ellen Daniels. "The first fire occurred

in 1828, another in 1854, and then back in 1924." "Luckily on a small portion

of the documents of marriages and a few birth records were destroyed,"

she added.

The year of Mary's birth would obviously have been 1835, so the possibility

of her birth records being lost loomed large.

A search through cumbersome historic volumes of deeds, aged marriage and

birth records, census reports and old cemetery rosters proved fruitless.

Without her last name, the beautifully scrolled pages of leather-bound

ledgers yielded no clues to Mary's identity.

The small town of Irwinton, the county seat, buzzed with the mystery. Typically,

word spread fast about the search. Local rural residents whose homes were

located within a few miles of the gravesite, provided the first connection.

Lynette and Charles Mixon came up with a name to trace the land ownership

by - Smith. The site of Mary's burial was on the old Smith family homeplace.

"We've

heard tales that she was a slave, " revealed Mixon. Information that Smith

family descendants still lived in the area refuelled another quest.

Back

in the vaults of the courthouse, the name Daniel Newman Smith (1818-1867)

emerged as the landowner. One of his great grandsons still lived in the

county nearby.

A visit

with Joe Smith started to unravel the mystery. The elderly man confirmed

that Mary was indeed a slave and that she had raised his grandfather after

the death of his mother when he was an infant.

Granddaddy

called her "Aunt Mary," Smith said. "He always said she took good care

of him and his brother and sister until she died. She was like a mother

to all of them, " the relative wistfully recalled.

"I

never knew her last name. If my granddaddy told me, I don't remember, "

he added. "Sometimes, you know, slaves would take the name of their masters,

but I don't recall if he said her last name."

Mack

Gray Smith (1853 - 1933) was the grandfather of whom he spoke. "He was

about nine years old when she died. They buried her there and he kept up

her grave until his death. I cleaned off the spot many times in my younger

years," the retired miner added.

Mary's tombstone

had weathered the years basically unharmed until the mining started. A

bulldozer broke the stone and overturned the slab. When it was set upright

again, it faced the wrong direction.

"My granddaddy's

father built that stone himself out of chimney rock (limestone), " said

Smith. The inscription etched on it is barely readable after 125 years.

"She was

sent to the Smith home at the tender age of 18 by the Spence family. Granddaddy

eventually married Rosa Spence, my grandmother. He told me stories about

Mary, but I don't recall how or why she died a such young age, " Smith

stated.

Historian

Victor Davidson wrote about a smallpox epidemic that struck in Wilkinson

County in 1862, the year of Mary's death. In his words, "It imposed a hardship

upon the people already overburdened by the Civil War"

Another historic

account by Joe Maddox told of the shortage of food and medical supplies

because of the war effort. That account told also of the loyalty of slaves

in support of the Confederacy.

Joe

Smith spoke of that loyalty, "Slaves didn't fare bad back then, not like

some people think. People were might good to them and they were loyal,

just like your family's loyal," he said.

Indeed,

what else could inspire such devotion from a young boy to his "Aunt Mary?"

What else could have aroused the memories of motherly love from someone

other than his own parent but love and loyalty despite the scar of slavery

on Georgia's history?

Although

the mystery of Mary wasn't completely solved, her story may be a lesson

from the past - that love transcended the barriers of race, creed, and

time. Her tombstone is a monument to that love.

Patricia A. Collins Copyright 1986

All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission of the author.

Website copyright Eileen Babb McAdams 2006 - 2007